Image above: Cattle grazing on the shores of Lake Chad (photo by Marina Bertoncin, 2011)

Andrea Pase, Angela Kronenburg García and Mariasole Pepa (University of Padua, Italy)

The rivers and lakes of the Sahel are a vital source of life, which, over time, have allowed many activities to flourish in rhythm with the ebb and flow of water over land: fishing, riverside and recessional farming, transhumant pastoralism, navigation and trade. A keen ability to resolve conflicts has allowed different communities of users to coexist, albeit not always peacefully, each finding hospitality in different space-time niches.

Since colonial times, large-scale irrigated agriculture has spread along the banks of these important wetland areas, occupying tens of thousands of hectares. Mega-projects brought with them an obsession with precisely defined space, within which everything was transformed for the purpose of agricultural modernisation: land was levelled, the hydrographic network was redefined, roads, warehouses and offices were built. In the process, existing uses, livelihoods and relations were displaced, replaced or restricted, particularly those of transhumant herders, who bring their livestock to graze on the banks of Sahelian watercourses during the dry season and droughts.

These and other dynamics are further explored in the book Water and Land in the Sahel, published by Routledge in July 2025.

You can access the entire, open access book here: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/oa-edit/10.4324/9781003429111/water-land-sahel-andrea-pase-angela-kronenburg-garc%C3%ADa-mariasole-pepa-marina-bertoncin-federico-gianoli-carla-braga.

Several chapters touch on aspects related to transhumance and mobility. Chapter 1 “Unfulfilled futures—One hundred years of large-scale irrigation projects in the Sahel” describes how large irrigation projects have become “traps” for humans and other than-human beings and entities in the process of terraforming (quoting Ghosh) that is inherent to colonisation. These traps frequently fail to “bring” development and the previously displaced activities reappear: transhumant herds, for example, create pathways through the heart of these projects to regain access to water and grazing areas. Their trampling causes the banks of irrigation canals to break down, thus contributing significantly to the deterioration of hydraulic infrastructure.

Three chapters (Chapter 10 “Sudan—A ‘picture’ of irrigation spaces before April 15, 2023”, Chapter 11 “Traces of irrigation—Some recent developments in the Chadian region” and Chapter 12 “The production of land insecurity and conflict in the Sourou Valley, Burkina Faso”) are devoted to the results of fieldwork.

In all three, transhumant mobility plays a central role. The case of Sudan is paradoxical; pastures that were taken away from pastoralists to make way for centre pivot irrigation, produce excellent fodder intended for export to the Gulf countries. Conflict between communities of users emerges clearly in two other chapters, each with a different approach; one more oriented towards legal institutions and the other towards political ecology (Chapter 13 “Land and water rights in the Inner Niger Delta—Between negotiation and conflict” and Chapter 15 “Changing patterns of resource conflicts in the Logone floodplains (Cameroon/Chad)—Between actors’ practices and development narratives”).

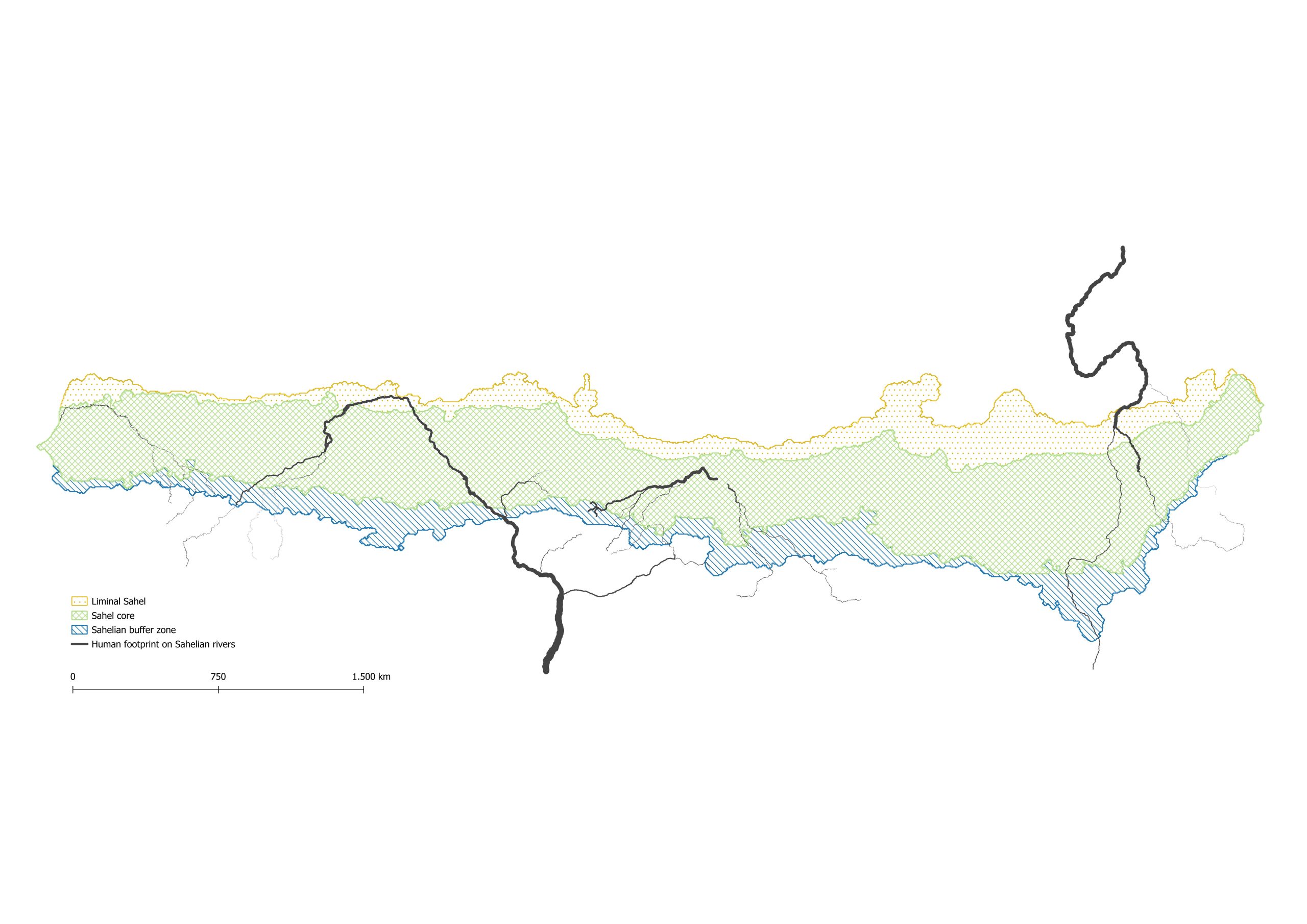

Another aim of the volume is to construct an innovative cartographic representation (or rather, a plurality of representations) capable of accounting for, on the one hand, the mobile and fluid dimension that innervates Sahelian spaces and, on the other hand, how infrastructure – the ways in which the territory is organised and made productive – limit movement within rigid and coercive cages, such as state borders and the boundaries of mega-irrigation projects (Chapters 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9).

The book concludes by attempting, in Chapter 16 and 17, to outline a “fluid research agenda” aimed at investigating water and land in a different way that highlights the profound need to value those mobile forms of interaction with space, such as transhumance and nomadism, that are best able to exist and thrive with and within the constantly changing Sahelian landscape.

We look forward to your feedback: you can contact us by visiting our website https://atlasahel.it/en/.

Andrea Pase, Angela Kronenburg García and Mariasole Pepa (University of Padua, Italy)

Cattle grazing on the shores of Lake Chad (photo by Marina Bertoncin, 2011)

A map representing “the breath of the Sahel” (https://atlasahel.it/atlasahel/#/viewer/openlayers/462)