Above image by Gonçalo Mota, RHE Initiative

Julio Sa Rego (RHE Initiative and CRIA-Centre for Research in Anthropology) and Ioana Baskerville (Romanian Academy – Iasi Branch)

On June 4th, Portugal inscribed transhumance in its National Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage. It is the continuation of the global process of recognition of the deep historical roots and socio-environmental benefits of transhumance in various cultures around the world. The most visible initiative is the inscription by 10 countries of the “Transhumance, the seasonal droving of livestock” file at the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

The term transhumance derives from the Latin “trans” (across) and “humus” (land); crossing the lands. Transhumance is a system of cyclical and seasonal herd mobility, guided by shepherds, between different grazing lands. It can be horizontal, between pastures at similar altitudes, or vertical, from foothills to high-altitude grazing areas. It may occur in winter and/or summer. Transhumance have played a significant role in the origin and maintenance of many European cultural landscapes, especially those in the mountains.

Transhumance brings several socio-environmental benefits. It contributes to food security and community well-being, supports sustainable pasture management and promotes biodiversity. In some cases, it directly aids in fire prevention and thus helps to mitigate carbon emissions resulting from wildfires, as in Portugal.

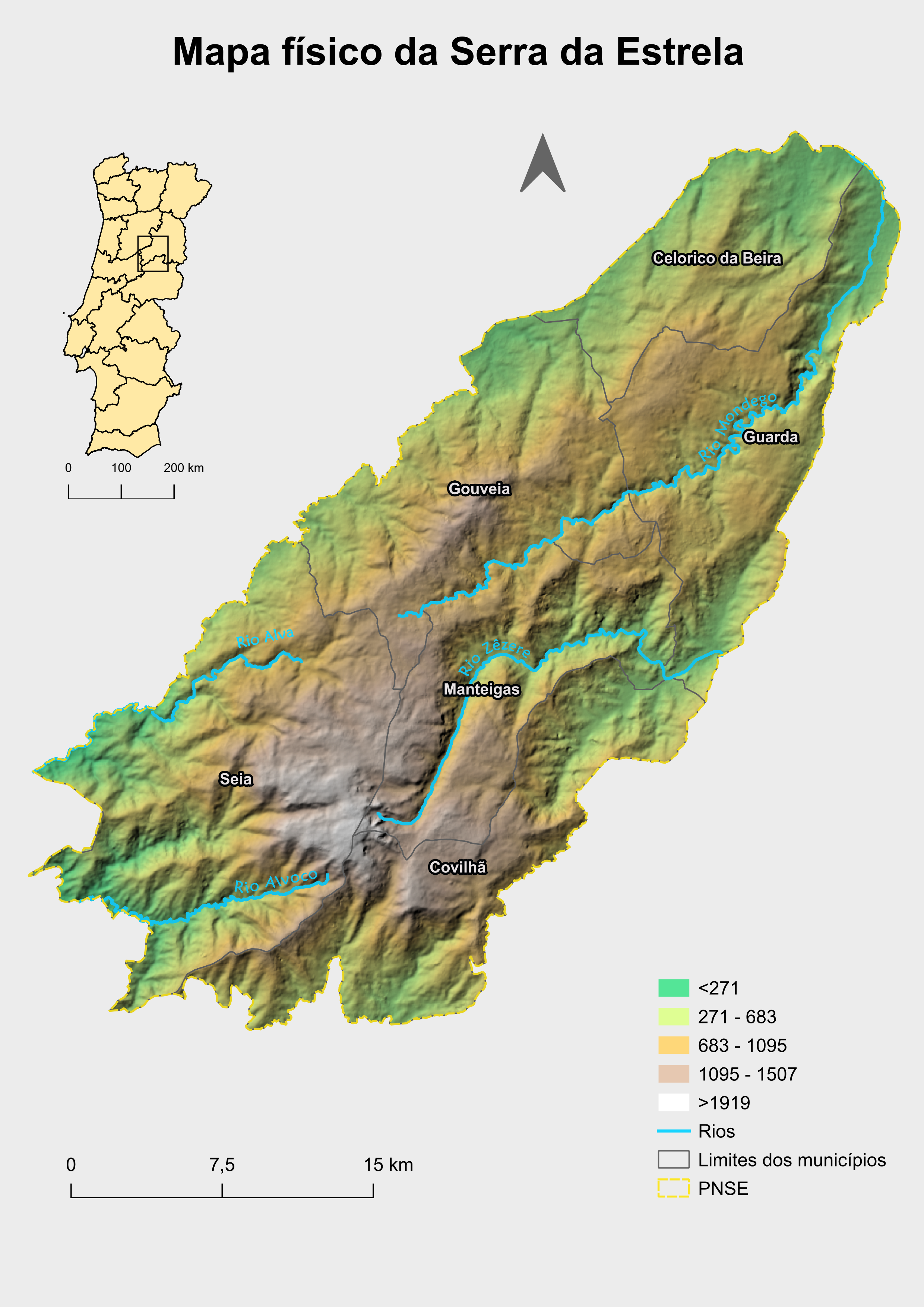

Transhumance in Portugal is closely connected to the Serra da Estrela region. It is a historical response to climate and landscape variability. If long-distance winter transhumance gradually disappeared through the 20th century (the last route disappeared in the 1970s), short-distance summer transhumance remained active in the territories of Seia, Gouveia, Manteigas and Covilhã municipalities.

Contemporary transhumance begins from April to June with sheep pilgrimages: adorned flocks travel on foot to local religious celebrations, where they are blessed by circling the village churches three times. The ascent happens between June and July. It takes up to two days and 40 kilometres to reach summer pastures at altitudes ranging from 1,000 to 1,900 metres. The summer season can last from 10 days to four months.

Today’s transhumance in Serra da Estrela, however, challenges the historical biophysical reasons for herd mobility. Both winter and summer transhumance were historically a rational response to the shortage of pastures. The high number of herds and the climatic conditions forced shepherds to move in search of food for their animals. Today, climate change and rural depopulation create a greater abundance of pastures in the lowlands. There would be no need anymore to go up to the Serra in the summer.

However, shepherds believe transhumance still benefits their animals. It provides cooler temperatures, fresher pastures, purer water, and air free from flies and dust at higher altitudes. Animals also enjoy more freedom, as they sleep outdoors instead of in stables. This mountain environment supports animal well-being and nutrition.

In addition to benefits for the animals, transhumance is good for the lowland pastures left behind. These lands get a chance to rest and regenerate, helping conserve vegetation and maintain the health of the landscape.

Transhumance in Portugal may thus be perceived as a cyclical ritual of animal purification and soil regeneration.

Julio Sa Rego (RHE Initiative and CRIA-Centre for Research in Anthropology) and Ioana Baskerville (Romanian Academy – Iasi Branch)